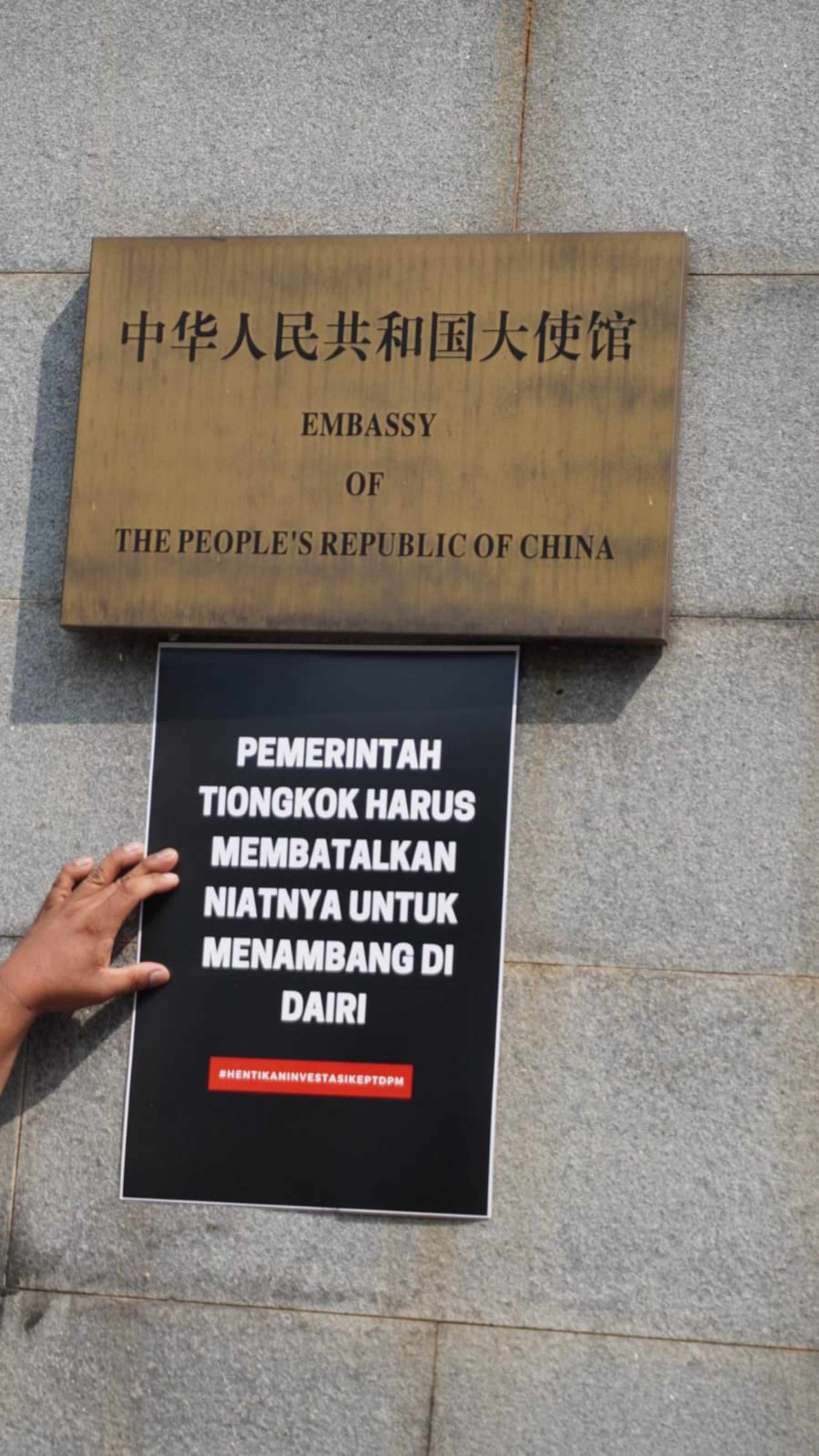

“We want the embassy to convey [to the Chinese government] that the majority of people reject the presence of the mine and that there is no need to provide loans to DPM.”

DPM is an Indonesian joint venture between mining giant China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Co (NFC) and Bumi Resources Minerals, a subsidiary of the Indonesian coalminer Bumi Resources, which is owned by the Bakrie Group.

NFC said on April 27 it had scored a loan of US$245 million from Carren Holdings Corporation Limited to DPM to develop the mine. Hong Kong-registered Carren Holdings is fully owned by Chinese state-owned investment company CNIC Corporation, whose 90 per cent stake is owned by China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange.

The protesters had sent a letter on Tuesday addressed to Wu Zhiwei, economic and commercial counsellor at the Chinese embassy, underlining the “serious and irreversible risks” posed by the planned mine.

“Multiple internationally renowned experts confirmed that there is a high risk that the planned tailings dam of the project could collapse. If this happens, a flood of millions of tons of toxic mine waste will kill many of us,” the letter said.

“We are shocked and concerned that China continues to develop and invest in such a disastrous project. We respectfully ask the Chinese government to … immediately halt any state-backed finance for the project and request NFC to immediately suspend any activities of this project.”

Tailings dams are embankments constructed near mines to store mining waste in a liquid or solid form.

The residents had in 2020 protested in front of the Chinese embassy in Jakarta and the Chinese consulate in Medan, but they were “particularly disappointed that the Chinese embassy has stopped communication with us since mid-2021”, the letter said.

The embassy did not immediately respond to requests for comments.

The mining mess

According to Medan-based North Sumatra People’s Legal Aid and Advocacy Association (Bakumsu), an NGO that provides legal support to communities, the zinc mining fiasco dates back to 1998, when DPM received mining concessions of 27,420 hectares (67,756 acres) in the Dairi. The area is estimated to contain about 5 per cent of the world’s zinc reserves.

Zinc can be used for consumer and industrial goods, including in electric vehicles. Last year, scientists from Australia’s Edith Cowan University found that batteries made of zinc and air, combined with new materials such as carbon, iron, and cobalt-based minerals, could power electric vehicles in the future as a better, more eco-friendly substitute for lithium-ion batteries.

If the project is realised, DPM plans to mix most of its mining waste with cement and inject it back underground, while the remaining toxic waste will be stored in a tailings dam covered by a 25-metre-high wall. But safety experts – commissioned by NGOs assisting the residents in their fight against the DPM project – said the planned dam would be vulnerable to earthquakes.

Experts cited in Bakumsu’s case briefing in 2020 noted the mine is located near the Sumatra subduction megathrusts, where the Indo-Australian Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian Plate, which has caused powerful earthquakes such as the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. It is also only 15km from the Great Sumatran Fault, which frequently produces significant earthquakes, further increasing the risk of disaster.

“A sudden tailings dam failure caused by an earthquake would send a wave of liquid mud over the region downstream to the north,” the experts said in the briefing.

The company also planned to build its waste dam “within 400 metres of the residents’ settlement, with churches and mosques where large numbers of people could congregate”, Bakumsu said.

Tongam Panggabean, director of Bakumsu, cited the example of a tailings dam breach in Brazil in 2015 that left 19 people dead and hundreds homeless, with villages destroyed and the river system polluted. The mining company involved, BHP, offered US$25.7 billion as compensation.

“Frankly, I’m surprised a Chinese government agency is getting behind the DPM project, given all these risks. There’s no upside,” Tongam said on Tuesday.

Keep on fighting

The residents have an ongoing appeal against the Indonesian government’s issuance of environmental approval to DPM at the Supreme Court, but the case is only at the stage of selecting the panel of judges, according to Monica.

The residents lost a previous court case in which they asked for public information regarding DPM’s work contracts, she said.

“We will still fight, because we think about our next generation, we don’t want to move,” said Monica, a mother of one. “It’s not that easy to relocate and adapt to the new environment. In the new place, we won’t necessarily have land as big as the land that we have in Dairi. Our lives will get worse if we give up our ancestral land for mining.”

Monica said the project was already affecting “social relations” in her village, Parongil, one of the 11 villages located downstream of the mine.

“Even now, the community in Dairi is already divided between supporters and opponents of mining. This shows that there’s already conflict in people’s lives. [If the project materialises], our culture will be eroded too, not to mention the environment being polluted by mining,” she said.

“We hope the loans that have been given by investors [to the project] can be cancelled because, when they fund this, they also fund the destruction of Dairi communities.”

إرسال تعليق